The country’s premiere defence research organisation, the DRDO (Defence Research and Development Organization), which has been spearheading all the defence-related research as well as development for the Indian armed forces, is all set for a major revamp since its establishment in 1958, if recommendations of a high-powered committee headed by a former Principal Scientific Adviser to the Prime Minister, K Vijay Raghavan, are accepted and implemented by the government. The committee appointed by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and consisting of experts from the three -armed forces, academia, and the private defence industry in India has given a full report to the government. After talking to all stakeholders, the Report has recommended several major changes in the functioning of the DRDO.

So, what will that revamp look like, and what will the restructuring of DRDO entail? BharatShakti has exclusively accessed some of the committee’s recommendations.

However, before delving into the detailed findings and recommendations of the report, it is essential to understand the underlying reasons that prompted the perceived necessity for an upgrade, restructuring, revamp, or potential division of DRDO into two distinct functions that can be assigned to a set of people nominated by the government.

The impetus for change arose due to DRDO’s extensive involvement in numerous projects on behalf of the armed forces, ranging from missiles and radars to underwater expertise, rockets, and ammunition, totalling around 900 projects. These projects, spanning various stages of development, are yet to be fully completed.

The committee identified a notable issue with DRDO—the organisation has become synonymous with delays, with a staggering 57 per cent of projects experiencing delivery setbacks. Numerous reports, commentaries, and analyses have portrayed DRDO as a laggard. The armed forces have consistently voiced concerns about the mismatch between their expectations and DRDO’s delivery promises.

That is precisely why the nine-member Vijay Raghavan Committee conducted a thorough analysis, quantifying the delays and identifying their root causes within DRDO projects. The committee revealed that these delays could be attributed to internal issues within DRDO. These internal challenges included inadequate resources, lack of expertise, insufficient management teams, or unavailability of necessary technology. The repercussions of these delays were substantial, leading to considerable costs for the country, with certain projects extending over 12 years and some having gone on for 18 years.

Hence, the Committee emphasised the imperative of addressing this problem as a top priority. According to the Committee’s findings, DRDO employs a workforce of 6,700 across 41 laboratories spanning various domains such as aero engines, radars, missiles, and electronics spread all over the country. To the Committee’s surprise, 50 per cent of the research and development budget used to be allocated to just two labs situated in Hyderabad and Bangalore. It found a skewed advantage for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), as well as scientists and development partners located in these specific regions. The Committee observed that this cosy arrangement has fostered a close-knit ecosystem between DRDO labs in these cities and individuals within that network. Recognising the need for a shift, the Committee underscored the necessity for a fundamental transformation in DRDO’s functioning.

Key Recommendations

Proposed Structure

Defence Technology Council (DTC)

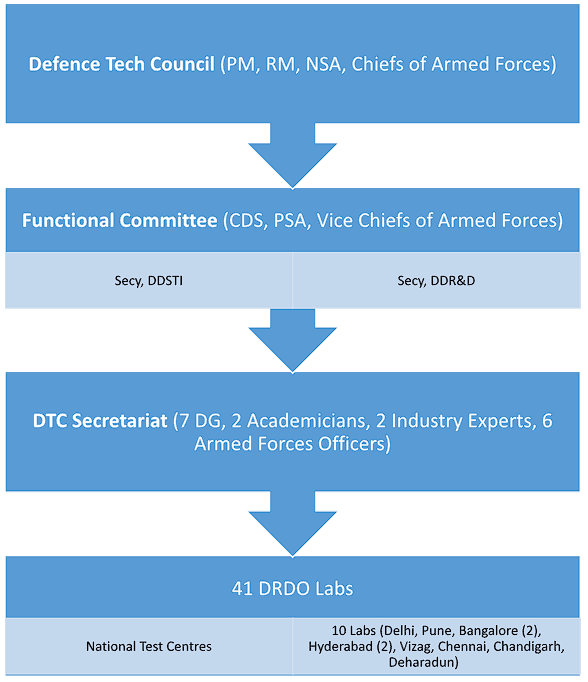

The Committee has proposed the establishment of the “Defence Technology Council” (DTC), which the Prime Minister would head. Its key members would include the Defence Minister, National Security Adviser (NSA), Principal Scientific Adviser, Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), and the Chiefs of all three armed Forces. Additionally, there would be representation from academia and industry, with two members each, ensuring a comprehensive and diverse perspective.

Apart from the apex body, the Defence Tech Council (DTC) would feature a functional Executive Committee led by the CDS, comprising Vice Chiefs of the Armed Forces. This Committee would play a crucial role in making project recommendations to the apex body. In addition to outlining the structure of the Defence Tech Council (DTC), the Raghavan panel has put forth a series of comprehensive recommendations aimed at transforming the functioning, efficacy, and delivery capabilities of DRDO.

Gist of Key Recommendations

-

- Two Secretaries

- Establish two verticals under Secretary DDR&D: one for DRDO and another for the Industry Ecosystem.

- Aim for improved coordination between DRDO labs and industries.

- Fast Induction of Next-Gen Technologies

- DRDO must focuse on next-gen technologies.

- Technologies, when proven, result in world-class products.

- Fast induction post-development enhances technologies for the armed forces.

- Two Secretaries

- Restrict Labs to 10

-

- Consider reorganising 34 of the 41 labs into 10 important establishments

- Convert the remaining seven labs into national test centres open to everyone for use

- Allow DRDO reorganisation to maintain operational and technological synergy.

- Collaborate with Industry

- Collaborate with industries during the development phase.

- Industries should lead product maturation after development.

- Concurrently process next-gen deep technology in both verticals.

- Implementation Commmitee

- Critically study the report.

- Form an implementation committee considering DRDO’s views.

- Analyze before implementation.

- Encourage Take-off Time

- Industry ecosystem is developing.

- Defense technology implementation takes time.

- Encourage take-off time for industry growth post-Atmanirbhar Bharat.

- Modify Processes and Policies

- Modify processes and policies for better DRDO performance.

- Critically evaluate and improve existing systems.

- Address HR Policy

- Address HR policy for scientist induction after 15 years of research.

- Focus on areas like procurement, HR, induction, and training for improvement.

- Address Non-Performance

- Deweed non-performers within the organisation

- Implement effective processes, a point not emphasized in the committee report.

In order to streamline the operations of all 34 laboratories, they will be organised into seven distinct clusters or groups, such as electronic or missile clusters. Each cluster will be headed by a Director General of the DRDO, the senior-most scientist. The Executive Council, responsible for deliberating and advising on proposed projects, will now include representation from these clusters. For example, in the Aero cluster comprising four labs, the senior director of one of those labs will assume the role of the cluster chief, as recommended by the committee. This restructuring is anticipated to bring about increased synergy among these clusters, aligning with the committee’s aspirations while formulating these recommendations.

Overhaul Recruitment Process to Infuse Talents

The panel identified a significant lapse in DRDO’s recruitment strategy, noting the absence of campus recruitment from colleges and universities. To address this issue, the committee strongly recommends initiating targeted recruitment drives from educational institutions, adopting priorities and specific criteria similar to the approach employed by the private sector during campus interviews. This shift is deemed essential because, as per the committee’s observations, the DRDO was getting the people who were left behind, who did not get a job or placement in the private sector, to join through the tedious UPSC route or separate advertisement route. Therefore, they came to DRDO only after exhausting the options of joining the private sector. Therefore, the panel emphasises the need for DRDO to actively engage in campus recruitment, thereby competing with the private sector to attract fresh and promising talents.

Furthermore, the committee suggests that Scientist B, which serves as the entry point for scientists within DRDO, should source directly from technical colleges instead of relying solely on cadre promotions within DRDO. The committee contends that expecting individuals promoted from within to deliver automatically may not be an effective strategy. Therefore, the committee recommends a comprehensive review and overhaul of the entire recruitment process.

The committee recommends a shift in DRDO’s recruitment approach by actively hiring talent from the private sector through open market channels, mainly targeting individuals with PhDs and postgraduate qualifications. The proposed strategy involves offering these recruits for specific projects and engaging them for a period of 3 to 5 years. After the completion of five years, 75% of these individuals would be permitted to leave, while the remaining 25% could be retained within the DRDO system. This approach mirrors the system employed by Agniveer in recruiting soldiers within the three-armed forces, where 25% of Agniveers are retained based on their performance, while the rest are allowed to explore opportunities in the open market.

Additionally, the committee advocates opening them up to the private sector for testing and utilisation. For example, the Chandipur integrated testing range for missiles in Odisha should be accessible to the private sector for activities such as firing practice, testing newly developed missiles, and other related endeavours.

The crucial point is that the DRDO is not shutting down but undergoing a restructuring to become more agile and efficient. The Committee emphasises the need for smarter and innovative operations. Notably, the Committee stresses that DRDO must align with contemporary requirements for effective collaboration with the armed forces.

The Committee underscores a paradigm shift in the armed forces’ outlook, advocating for collaborative planning where both entities jointly formulate and execute plans. Instead of independent initiatives, this approach aims to ensure synchronisation and avoid instances where the armed forces are presented with pre-developed platforms or equipment.

The focus is enhancing coordination and prioritising research and development over the production of research equipment. Unlike the corporatisation of the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB), the Committee does not propose such a drastic change for DRDO. It is expected to continue receiving its budget from the government, with an emphasis on utilising funds wisely to achieve the desired results.

It marks a positive step towards aligning R&D with the private sector for effective project planning and co-production. The Committee’s recommendations provide a roadmap for DRDO’s evolution, and whether the government will promptly adopt these suggestions or engage in further consultations remains to be seen.

Team BharatShakti

3 Comments

Thushar

I fear this committee report too shall end in the bin. With elections coming up, Govts priorities are likely to be elsewhere. If the current govt doesn’t return to power then there is absolutely no chance that these recommendations will see the light of day

Even if the present govt returns to power I doubt they’ll be able to discipline the bureaucracy well enough to force them to implement these reforms.

Mahen

I see it in a different way, I think if the current regime resume back they will come up with the new version of DRDO as they find lacks in it, Some necessary projects like AMCA is yet waiting, we are already behind in fifth generation game not just DRDO but HAL need to speed up, ADA & other similar institutions need to be revamped, we need to be 100% indigenous it shouldn’t remains limited upto designing & metals only if you will remain dependent for engine, avionics, radar, ejection seats, etc then in case of war this will create problems, hoping to see great things happening, optimistic as usual

Man Mohsn Pandey

The core issue was that DRDO instead of concentrating in R&D was busy in realization, testing, field Trials of the systems (about 90% of manpower was busy in these activities). Second was nexus between DRDO scientists and the Private vendors leading to corruption. These vendors were designated as Production partners and the DPSUs were forced to buy from these vendors at highly inflated costs and poor quality. The DPSU were not allowed to develop alternate vendors. This led to rampart corruption and very high cost of equipments for the end users.