Editor’s Note

The South China Sea has been boiling for some time now. As tensions flare-up in the South China Sea (SCS) the prime contestants seem to be Vietnam and China. Both countries have been locked again in a stand-off lately, contesting each other’s claims of maritime rights and seabed exploration endeavours. This article, while presenting the SCS narrative fairly comprehensively, also assesses the possible implications for India by tracing New Delhi’s interests in the SCS and identifying measures that India could take to secure its interests there.

——————————————————————————————————

Since 4 July another chapter of confrontations has been simmering between Vietnam and China over fuel and maritime resources and in the South China Sea. The renewed tensions repeat a familiar pattern the world has witnessed repeatedly regarding Chinese conduct in the South China Sea disputes. It enhances the fragility of the situation between the claimant states in this strategic expanse of sea waters.

Reports in recent days have suggested a large-scale stand-off between several coastguard ships of both countries when a Chinese oil exploration ship entered the contested waters near the Spratly Islands. Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post newspaper reported on 12 July that six “heavily armed” coastguard vessels, two from China and four from Vietnam, had been eyeing each other since the beginning of July.

Vietnam – China Showdown

The standoff ensued near oil blocks that lie within Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), where a Chinese seismic survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 (Marine Geology 8) escorted by a number of Chinese Coast Guard and fishing vessels, has been conducting activities that Vietnam says violate its EEZ and continental shelf. Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry said that Hanoi had demanded that China stop the “unlawful activities” and withdraw its ships from Vietnamese waters.

Image Courtesy: Reuters

Hanoi has accused Beijing of violating its sovereignty by sending a survey ship to Vanguard Bank, which sits within Vietnam’s UN-recognised 370 km (nautical miles) exclusive economic zone. The coastguard and survey vessels have been loitering near a new Vietnamese drilling rig. The platform has been contracted from Russia to exploit the oil and gas reserves beneath. The Chinese ship allegedly conducted high-speed manoeuvres near two Vietnamese offshore supply vessels on 2 July, passing within 100 meter of them and less than a kilometer from the rig.

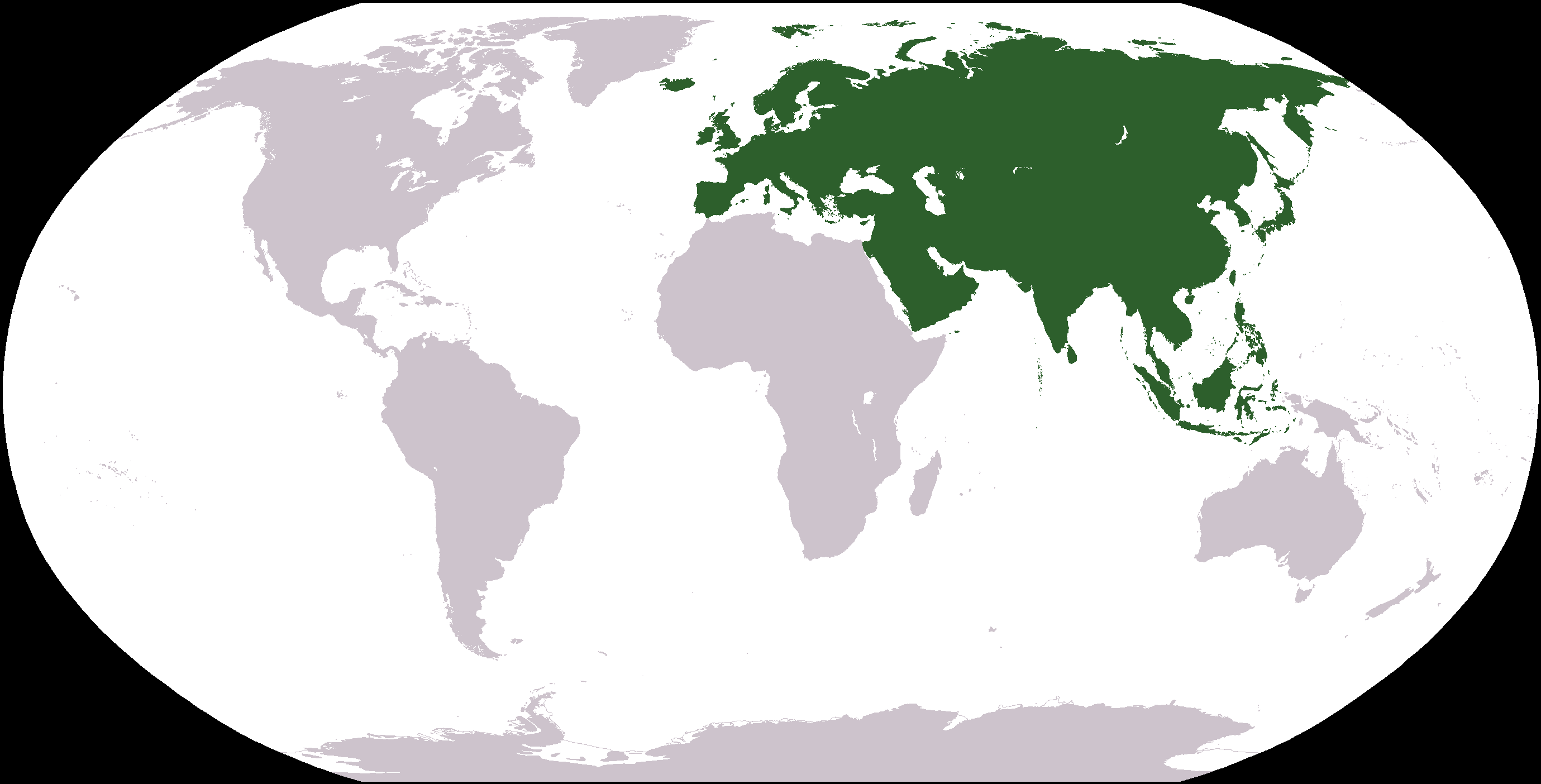

China claims almost the entire SCS as its own, a claim that is strongly contested by countries like Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Taiwan, leading to many face-offs. Beijing invokes its so-called U-shaped “nine-dash line” to justify its historic rights to the waterway, including large swathes of Vietnam’s continental shelf where it has awarded oil concessions. Beijing has resisted subjecting its territorial claims to international tribunals and instead reclaimed and installed military facilities on disputed islands.

The line runs as far as 2,000 km from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometres of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. The Chinese survey ship appears to be engaged in high-resolution mapping of the seafloor. As the Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducted its survey, nine Vietnamese vessels closely followed it. Chinese Foreign Ministry warned Hanoi to “respect” Beijing’s sovereign rights and jurisdiction, “and not to make any move that may complicate matters”.

That seems unlikely. In a statement published on the Vietnam Coast Guard website, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc told sailors to “stay vigilant and ready to fight” and to be alert for “unpredictable developments”.

In 2014, tensions between Vietnam and China had risen to its highest levels in decades when a Chinese oil rig started drilling in Vietnamese waters. The incident triggered boat rammings by both sides and anti-China riots broke out throughout Vietnam.

Oil exploration in the South China Sea is a highly emotive issue in both countries, which fought a series of violent disputes between 1974 and 1988.

Vietnamese fishermen took this picture of the Chinese survey ship. The Chinese ships continue to operate in Vietnam’s jurisdictional waters.

In recent months, due to increased Chinese activities and re-assertion of claims the oil exploration vessels and fishermen from the Philippines and Vietnam have stated that they have been at the receiving end of considerable Chinese harassment in the South China Sea area. The consequent protest by these two countries is probably one of the primary reasons which led the United States calling for an end to China’s “bullying behaviour”. “China’s repeated provocative actions aimed at the offshore oil and gas development of other claimant states threaten regional energy security,” the US State Department said in a statement recently. The United States has long called for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, and on 18 July informed that it had sailed a warship through the Taiwan Strait.

The statement was viewed from varying perspectives by different quarters. While it undoubtedly displeased the Chinese, such an American opinion was viewed with considerable relief by the other affected countries especially Vietnam and the Philippines.

American Interests in South China Sea

The US interests in the SCS fall into three broad categories; first economic interests tied to the sea lanes, second defence ties with allies and other security partners and lastly implications for the global balance of power and influence. In each of these arenas, a successful Chinese effort to seize control of the SCS will have a profound impact and each is worth elaboration.

Busiest Sea Lanes

The sea lanes that pass through the SCS are the busiest, most important, maritime waterways in the world. These routes carry one-third of global shipping with an estimated value of over $3.4 trillion. In the bargain, it also accounts for nearly 40 per cent of China’s total trade and 90 per cent of petroleum imports by China, Japan, and South Korea and nearly 6 per cent of total US trade. For India, the SCS is important as 55 per cent of its trade passes through it. These same sea lanes are a vital military artery as the US Seventh Fleet transits regularly between the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, to include the Bay of Bengal.

Strategic Defence Ties

America has formal defence security ties with five Asian countries; Japan, South Korea, Philippines, Thailand, and Australia. Besides, the United States has affirmed some responsibility for the defence of Taiwan and has close security ties with Singapore and New Zealand. Beyond that, there are a variety of formal security cooperation agreements with Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Cobra Gold, hosted by Thailand and led by the United States, is the largest annual multilateral military exercise in Asia. The US has built and maintained a huge network of security links and obligations throughout East and Southeast Asia all sustained by regular contact with the Seventh Fleet as it transits the region via the SCS.

Regional Balance of Power

The most important stake in the SCS concerns the preservation of a regional “rules-based” order supported by the US. This order embodies certain foundational political principles; respect for international law, preservation of sovereign independence of regional states, a refusal to legitimate unilateral territorial expansion and the unconditional acceptance of the sea lanes as global commons.

If China succeeds, in displacing American power in the Western Pacific and Chinese territorial expansion into the SCS becomes permanent and codified, global geopolitics will have entered a new and very different era. Southeast Asia will inevitably be rendered subordinate and compliant to China’s will. Australia will be isolated with an uncertain future. Japan and South Korea will face a perilous new reality with China in control of the seaborne lifeline of both countries. The credibility of the US security support for allies and partners will be shredded. India will lose its current freedom of access through the SCS and much of Southeast Asia. European access to Asia will be Beijing’s call.

All these challenges will occur in a region that is increasingly the vibrant centre of the global economy. The Chinese message is loud and clear; the era of American international leadership and predominance is over and a new preeminent power has taken its place. In nutshell, the SCS is the immediate arena where two alternative geopolitical paradigms are contesting for supremacy.

Indian Interest in South China Sea

India has vital economic and strategic interests in the SCS as crucial sea lanes of communication pass through the region. Over 55 per cent of India’s trade passes through the Malacca Straits and SCS and thus New Delhi has a keen interest in these key waterways remaining free and open. In fact, India has publicly supported freedom of navigation and flight in the SCS based on international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Hague Ruling of 2016 (China has “no historical rights” based on the “nine-dash line” map) in favour of the Philippines.

The Nine-Dash-Line in the South China Sea. Picture: Twitter

The SCS region is rich in oil and hydrocarbon deposits, holding approximately 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, according to the US Energy Information Administration. Though India imports most of its crude oil from the Middle East, due to protracted conflicts in the region that can flare up at any time and the recent US sanctions on Iran, India is eager to diversify its imports. SCS holds significance for an energy-hungry New Delhi.

To secure these economic and strategic interests in the SCS, India is deepening its relationship with ASEAN countries, especially those who dispute China’s presence in the SCS. For instance, the state-run oil firm of Vietnam has awarded India two offshore fields in the contested waters of the SCS to explore hydrocarbon reserves. India has also been increasing maritime cooperation with ASEAN countries in the past two decades, such as by conducting joint coordinated patrols with Thailand and Indonesia and an agreement with Singapore that would allow India to access the Changi Naval Base, close to the disputed SCS, for logistics and refuelling purposes.

Vietnam Most Determined Rival of China in South China Sea

With energy resources being the main rationale behind the Chinese claims, China has bitterly opposed oil companies from exploring in disputed areas which are currently not under its control. It has warned international oil companies from exploratory operations off the coast of Vietnam, claiming that this encroaches on its territorial sovereignty. But Vietnam, occupying more than twenty of the Spratly Islands, has refused to be cowed down by this browbeating big neighbour and has worked despite the protests, reinforcing the international opinion that Vietnam is one of the most determined rivals of China in this region.

Over the years due to the enhanced tension in the region, the Vietnamese National Assembly approved a maritime law claiming sovereignty and jurisdiction over the Paracel and Spratly islands in the SCS on 21 June 2019. The perception of the Vietnamese side was that this was merely a continuation of several provisions in their existing laws, however, the Chinese viewed this development with considerable concern and a violation of their sovereignty.

In a retaliate measure, the same day China announced that it had elevated the administrative status of the Nansha (Spratly) and Xisha (Paracel) islands from a county to that of a prefectural-level district.

Further actions by the Chinese followed after two days when on 23 June 2012, the state-owned company CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Company) offered nine offshore blocks, located in what Vietnam claimed was its exclusive economic zone, to international oil and gas companies for bidding.

It signified a Chinese sovereignty claim over the seas that was a mere 100 miles off from the shores of Vietnam and around 350 miles from the nearest undisputed Chinese territory of Hainan Island. Importantly, these blocks on offer by the Chinese overlapped the blocks that had already been sold by the Vietnamese earlier for exploration.

However, this ongoing action did not prevent the Vietnamese from going on the verbal offensive against the move and it urged foreign companies not to bid for these offshore blocks as they lie deep inside its continental shelf.

Implications for India

The current growing Chinese provocations are in direct conflict with India’s interests. The Indian company ONGC Videsh (OVL) has been operating in Vietnam’s EEZ. In 2006, it won the international bid to explore Blocks 127 and 128 (Phu Khanh Bay) in the territories under dispute but within the Vietnamese EEZ. Subsequently, India chose to withdraw due to technical reasons. However, the Indian operations in Block 06/1 in the region continue to date.

Image Courtesy: LiveMint

Vietnamese diplomatic sources at New Delhi said the Chinese ships came close to areas where India’s ONGC has oil exploration projects. According to sources, OVL oil Block 06/1 is located close to the area where Chinese and Vietnamese vessels have been engaged in a standoff since July 4. The oil block is barely 10 nautical miles from Vietnam’s baseline and is located in its continental shelf as stipulated in the 1982 UNCLOS, sources added. Joint ventures between Petro Vietnam (PVN), Russia’s Rosneft and India’s ONGC Videsh (OVL) for oil and gas production have been in place for 17 years in these waters, the sources disclosed.

China has been objecting to India’s oil exploration projects in the Vietnamese waters in the South China Sea which is unlawful and violate Vietnam’s sovereign rights over its water, said sources. Consequently, Vietnam briefed India about the current situation in the SCS as it is a major stakeholder and a key player in the region. Vietnam has sought stronger condemnation and action on the South China Sea issue from its comprehensive strategic partner – India.

Breaking the studied silence on the Vietnam-China stand-off, New Delhi said India’s oil exploration projects were going on in the area.”I do not think there has been any stoppage to our oil exploration,” said External Affairs Ministry Spokesperson Raveesh Kumar, when asked about the status of Indian oil exploration in the area in the wake of tensions between China and Vietnam.”We have genuine and legitimate interests in the peace, stability and predictability of access to the major waterways in the region,” he said.

India has been supporting freedom of navigation and access to resources in the SCS in accordance with principles of international law, including the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. In January 2015, PM Modi and then US President Barack Obama issued a landmark Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region, which explicitly referenced the SCS and called upon all parties to ensure freedom of navigation and resolve disputes according to universally recognised principles of international law, notably UNCLOS.

Conclusion

While trying to keep at bay “foreign powers” from the SCS region, China has managed to unnecessarily antagonize all well-meaning and affected maritime powers including the US and India who seek stability in the region and freedom of navigation. Summed up, the South China Sea region has emerged like a proverbial tinder box awaiting to explode. With ineffective diplomatic solutions, disunity amongst ASEAN nations, military build-ups, face-offs, brinkmanship etc., the potential for a full-fledged conflict enhances manifold unless all nations concerned are willing to take drastic measures.

By Ravi Shankar

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of BharatShakti.in)

One Comment

Pratap Sekhon

A well articulated write up. It touches upon various currently relevant and emerging geo political aspects of SCS issue. Brief, concise yet covers significant details.